Hacking the Meatmeet BBQ Probe — Part 2

We break down the Meatmeet Android app and find a number of vulnerabilities including: hard coded credentials, insecure memory management, and an open storage bucket.

In Part 2 of this hardware hacking series we are turning our attention to the mobile application. From the application, each Meatmeet owner controls their probe and base station, allowing them to cook their meat to perfection. We can even share these devices with other users, allowing our friends, (I suppose?) to watch our meat cook too. All of this is done over Wi-Fi and Bluetooth. To perform our analysis of the mobile application, we pulled the APK using Android Debug Bridge (ADB) to our local host and decompiled it with jadx.

Static Analysis

More Wi-Fi Credentials!

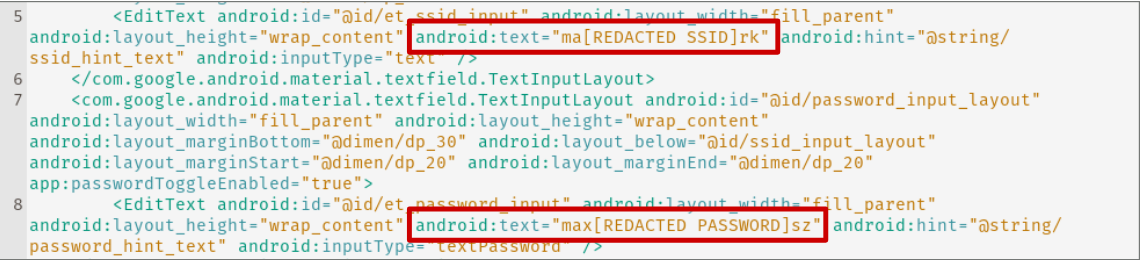

As we had (likely) found the Wi-Fi credentials used by the manufacturer of the Meatmeet probes still in the NVS in part 1, we decided to check the mobile application as well on the off chance that they may have stored them there as well, perhaps to speed up mobile application testing. Sure enough, our hunch was right; within the content_wifi_config.xml file we found the same set of credentials saved.

Cleartext Traffic

The AndroidManifest.xml file can be a gold mine for information about the application and vulnerabilities. Essentially, it contains a number of configuration details, settings, and permissions which are required for the functionality of the application. You can find more about them here. Many applications like MobSF, or as we’ll see later in the article APK Components Inspector, rely on this file to find misconfigurations and vulnerabilities which we can try to exploit.

If for some reason your application must communicate with servers over HTTP, that setting would have to be configured within this file. We found that setting enabled for the Meatmeet application and, importantly, there were servers with which the application communicates over HTTP.

By running a grep for http:// we confirmed that there were some endpoints called in the normal operation of the application that use the unencrypted protocol.

An attacker could exploit this to intercept the communications between the user and the Meatmeet servers, which may result in a compromise of their user account.

Dynamic Analysis

Interception and Password Hashing

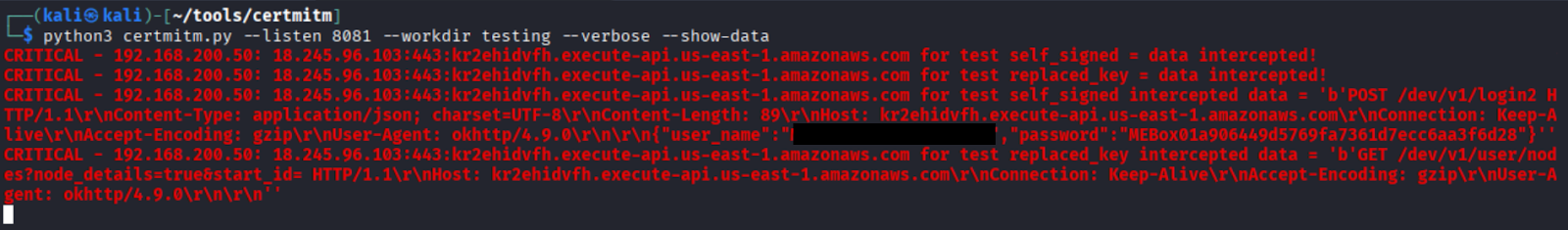

What first caught our eye when we fired up the application was the fact that, despite not having installed a Burp Suite certificate on our test phone, we were able to intercept all of the traffic coming from the Meatmeet mobile application. While some was HTTP, as we saw above, most of the communications were over HTTPS. This was quite handy since it can be a bit irritating to properly install certificates on newer versions of Android.

This obviously makes our lives easier, however it also means that someone with control of an upstream proxy or in a position to MITM our traffic could use a tool like certmitm to decrypt our TLS traffic and view the data, just as we had in Part 1 of our Hacking Furbo series.

You may also notice that there is a strange encoding on the password in the above screenshot. For whatever reason, Meatmeet has decided to prepend the device name: MEBox01, to a MD5 hashed password—MD5 is far from the most secure method of hashing passwords in 2025. Password-Based Key Derivation Function 2 (PBKDF2) is recommended by National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and would be a far more secure option for passwords.

Request Signing

As we walked through the application, we observed that API calls were made to two servers. The first of these handled everything related to the device; we determined that this is an implementation of Espressif’s Rainmaker API services based on the endpoints which were called—the official documentation for Raimaker can be found here. This would correspond with the MQTT Rainmaker service we saw in part 1.

The second one handled things related to the user profile: name, email, photos, etc. While interacting with this API we noticed that each request included a random nonce, timestamp, and signature to ensure it could only be sent to the server once.

Any attempt to replay the request would return a 500 error in the response body.

This severely limited our ability to test each endpoint or modify the content of requests as they come through. In order to build a workaround, we had to determine how this was being handled by the mobile application.

Some grepping of the decompiled APK revealed that this signature was being generated by the createSign method seen below.

This createSign method signs the message by calculating the signature with the following values:

Sign = MD5("20250103" + appId + "e65d015594810c740155fc99cb2cd7e4" + nonce + timestamp [+ token])As we saw, the signatures are good only for one use. So, each time we wanted to send a new request we had to generate a new signature. Thankfully, Python allows us to quickly replicate this process.

import hashlib, random, time

SECRET = "e65d015594810c740155fc99cb2cd7e4"

TAG = "20250103"

ALPHABET = "0123456789ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVXYZabcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz+/"

def random_nonce(length=10):

return "".join(random.choice(ALPHABET) for _ in range(length))

def create_sign(app_id, nonce, timestamp, token=None):

base = TAG + app_id + SECRET + nonce + str(timestamp)

if token:

base += token

return hashlib.md5(base.encode()).hexdigest()

# Usage

app_id = "com.idrawgear.temp01"

nonce = random_nonce()

timestamp = int(time.time())

token = "" # JWT token seen in the Authorization header

sign = create_sign(app_id, nonce, timestamp, token)

print("Nonce:", nonce)

print("Timestamp:", timestamp)

print("Sign:", sign)

Rather than running this script in a terminal every time we want to replay a request, we decided to use a Burp Suite plugin developed by one of our team members: Burp Suite Hotpatch. This runs the operation and replaces the values each time a request is replayed, sent with active scan, or even intruder. It’s very handy and an extremely powerful extension.

Profile Pictures

Our next area of focus, after having configured our request signing, was the file upload mechanism for profile pictures

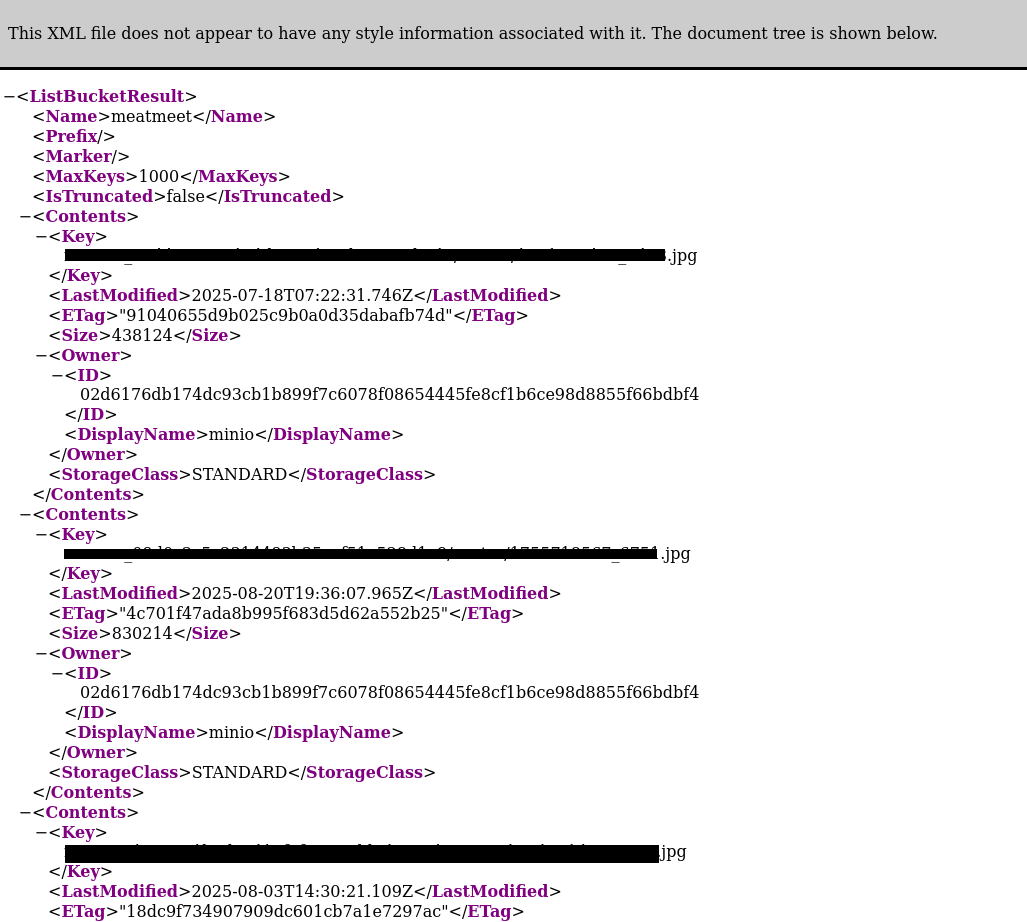

Whenever we test an application, whether it’s mobile or web, we pay keen attention to the file upload process. The Meatmeet was no exception. File uploads are notoriously vulnerable to a variety of misconfigurations. In this case, we noticed in the above response that the file was referenced without a pre-signed AWS S3 URL, or any other sort of authentication or authorization. This piqued our interest.

Navigating to the URL, and trimming off our unique identifier, we found the bucket was misconfigured to allow the listing of every user’s profile picture.

A quick count gave us 72 users who had uploaded pictures. This may not be the largest exposure, but we doubt that these users expected their pictures to be retrievable by anyone. We have redacted the URL and their IDs to protect the privacy of these users.

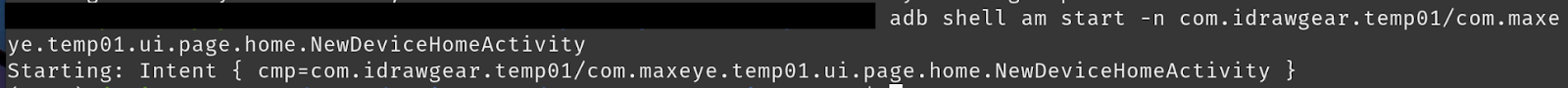

Exported Components

APK Components Inspector has become a favourite tool of ours for the analysis of Android mobile applications; running it on an APK will return a list of exported services, activities, and providers, as well as the commands to attempt to exploit each of them. Here was the full listing of exported components for the Meatmeet mobile application.

Once the script finishes analyzing the APK, we are returned the full listing of commands which we can subsequently copy and paste into our terminal to attempt to exploit any of the exported components.

This is all done over ADB, however in a real-life scenario a malicious application installed on the device could also trigger these commands.

It was through testing these that we discovered we could bypass the login screen when a user had recently signed in to the application.We authenticated to the app, logged out, and then swiped up to terminate it. After which we executed the following command over ADB:

This would re-open the app and allow us to gain access to the authenticated session.

We determined that this was possible because of two issues. Firstly, by monitoring the traffic through Burp Suite we discovered that the token which is used to authenticate our session with the API handling profile information is not invalidated when a user logs out. This means that this attack can be performed for the lifetime of that token and, as we’ll see later, these tokens can be found in memory on the device.

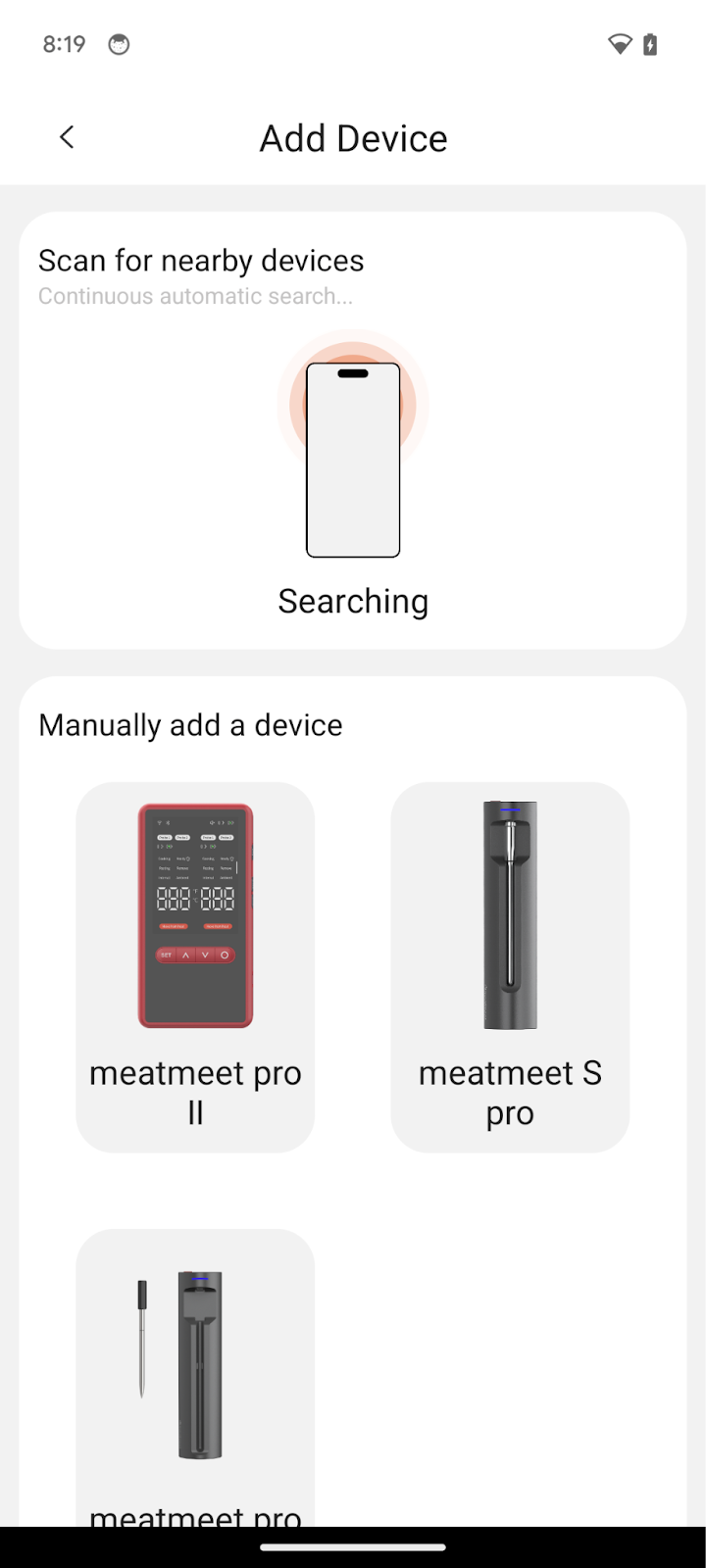

We were also able to find an unreleased Meatmeet device by exploiting the exported activities. By running the following command we opened an “Add Device” window which displayed the Meatmeet Pro II, a device which we can find no other information about online. It’s worth mentioning that this “Add Device” page was never opened during the normal flow of connecting a device to our account.

Memory Dump

After having interacted with the application quite a bit, we decided to take a look at how it was handling the storage of information in memory. All mobile applications must store sensitive information in the device’s memory in order to function properly. The user’s credentials, authorization tokens, and other information will all reside there so that the session can be maintained during normal use.

The issue is when this memory is not correctly freed after an application is terminated, leaving residual data which can be accessible. When performing memory dumps you must pay special attention to the state of the application.

There are two interesting points at which to do a memory dump:

- Walkthrough → Log out of application → Close application → Open application → Perform memory dump

- Faced with a challenge prompt → Perform memory dump.

If you can find credentials in the first case, or the prompt answer in the second, you can bypass whatever “blocker” you’re faced with. In the case of the Meatmeet mobile application, the only “challenge prompt” we had available was the login page so we went for the first path.

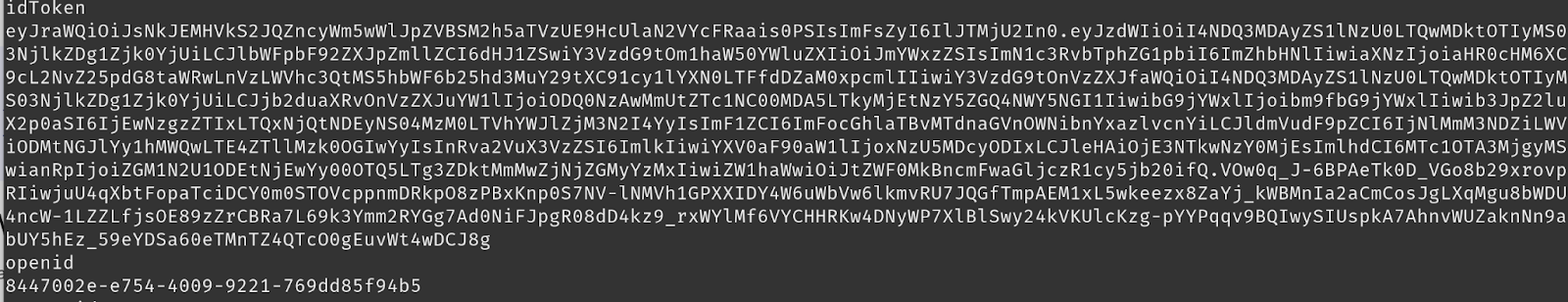

We knew some of the sensitive details to look for when searching the dump, like our email and hashed password, but others such as the current JWT required us to proxy the traffic and make a copy from that session. After having terminated the application we used Fridump3 to retrieve the contents of memory.

Once the dump is completed, we can either search the strings file which is generated by Fridump or grep the entire directory. Our first find was the idToken used for the Espressif API server.

We also discovered the JWT used by the other server which confirmed why we could regain access to the application after logout with the exported activity.

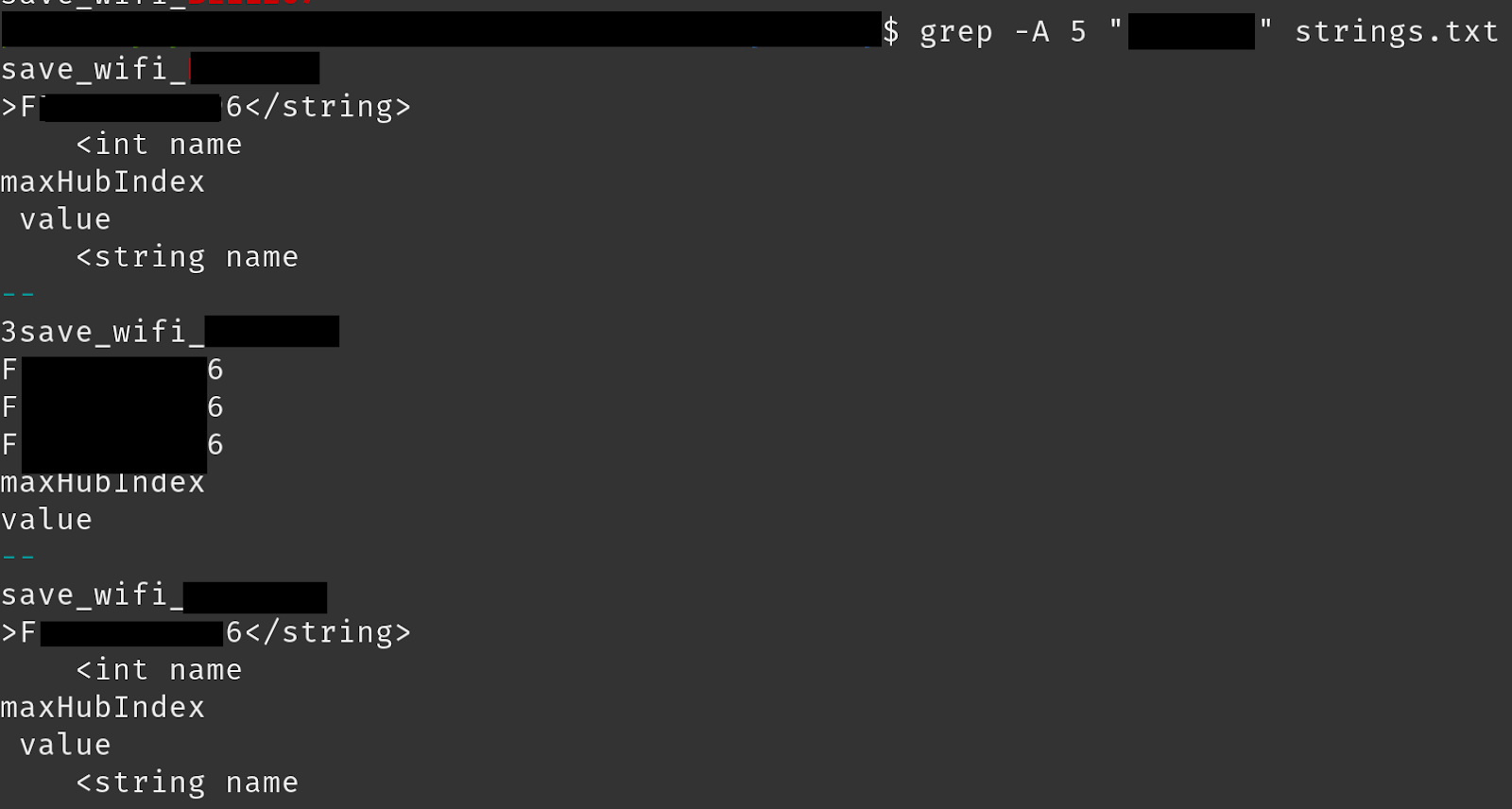

Arguably, the most sensitive information handled by the application is the Wi-Fi password for the network that we connect the probe base station to, an adversary would be much more interested in getting access to your home network than your meat thermometer; and sure enough we found that in memory as well. Excuse the copious redactions.

We confirmed this information was retrievable by other users as well, not just by performing a memory dump.

After configuring the Wi-Fi for our device we logged out, terminated the application, and re-authenticated as another user. Upon registering the new device to this second account we were presented with the form to authenticate to our access point, with the SSID and password pre-filled.

With that, we conclude part 2 of the hacking Meatmeet blog series. We found a number of hidden gems and some pretty serious misconfigurations. We hope you enjoyed this adventure into the application and learned a thing or two about hacking Android mobile applications. In the next part of the series we will conclude with the most interesting attack vector of all: Bluetooth Low Energy. In part 3 we reverse the GATT characteristics, identify some of the ways to interact with the device, and build a BLE BBQ botnet!

.avif)