Hacking the Meatmeet BBQ Probe — Part 1

We dismantled the Meatmeet Pro, monitored its BLE and network activity, and dumped the ESP32 flash for analysis.

After completing our research on the Furbo 360 and Furbo Mini devices, we found ourselves looking for the next hardware hacking target. While perusing Amazon one evening we finally settled on a device: the Meatmeet Pro wireless meat thermometer.

Device Tear Down

The Meatmeet devices come in two parts: the base station and probe. The base station is what will be connected to your Wi-Fi network, allowing you to monitor the probe which is connected to the base station over Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE).

Our first task was simple: tear it apart. We were able to deconstruct the base station device fairly quickly and gain access to the PCB. On this PCB we found a number of exposed test pads, the most important ones for our testing were TX, RX, and GND. These would allow us to monitor the device’s UART logs. We also discovered that the device was running on an ESP32-C3-1U mini chip.

Traffic Analysis and UART

Our next step was to analyze the network traffic to and from the device. To do so, we used Matt Brown’s mitmrouter and fired up Wireshark, just as we had done in our Furbo research project. While watching Wireshark we also connected to the device over UART to get a better idea of what was going on.

The UART logs were fairly verbose and allowed us to better understand what we saw on Wireshark—while the device was communicating with the AWS IoT server on port 443 it was doing so using MQTT and not over HTTPS as one might expect. Typically, MQTT connections are done over 1883 or 8883 so this was a bit of a surprise to us.

Other than what we saw on UART, we had very little to go off of at this point. No services were exposed on the device and the only network protocol in use was MQTT.

Flash Dump

While ESP32 binaries are notoriously challenging to reverse engineer, we decided to dump the flash and see what we could find out from the data stored on the device. In order to get the chip into a state which allows reading and writing we needed to enter the bootloader mode. To do so, we would have to “bring low” the IO9 test pad—this can be done by connecting the pad to ground.

With our PCBite probes this was a fairly simple task. We could connect TX, RX, and GND, as per usual, to our Serial-USB adapter. Next, we connected the second GND pin on the probe to another probe touching IO9. It made for quite a mess of cables as we can see in the picture below. Given how small the chip is, it required very precise work.

Once this was done, all we needed to do was power up the device and we’d be able to run esptool to dump the flash.

ESP flash dumps are a bit more tricky to analyze than your regular firmware. Thankfully, Wilco Van Beijnum (wilco375) created the ESP Toolbox and documented how to use it in his talk, Breaking And Remaking ESP32 Devices: A Guide To Reverse Engineering And Patching. As it was our first time attempting to analyze an ESP32-based device it proved to be a very helpful resource, we highly recommend checking out both the toolbox and talk!

Using espknife.py we parsed the flash file into its various segments.

These were written to the parsed directory, the contents of which can be seen below. From this we can see the flash contained several partitions: the bootloader, NVS, phy, ota_0, ota_1, and fctry.

The Non-Volatile Storage (NVS) is where key-value pairs of data are stored on a device. Essentially, this is where whatever user-configured data a device may use in its operations is kept.

We decided to first try to see what strings (every reverse engineer's favourite tool) would return when run on the NVS partition. Lo and behold, we found the certificate and RSA private key used to authenticate to the MQTT server!

We then ran Espressif’s nvs_tool.py on the NVS file to extract the contents into a more readable format that includes some additional context about each record. What we found was a ton of data, including our own previously configured Wi-Fi credentials, which is to be expected.

What we didn’t expect was this:

Within this NVS partition we found what is likely to be the Wi-Fi credentials of the company we determined to be the manufacturer of these devices. While they are in this “Bitmap State : Erased”, meaning they will eventually be removed, we were still able to find them in the dump before they were removed. They have been changed to this state as we have configured the device to connect to our own network, resulting in the previously configured credentials being moved to an erased state before being cleaned up later on.

Unfortunately, their offices are located overseas so we can’t validate whether or not these actually work.

espefuse

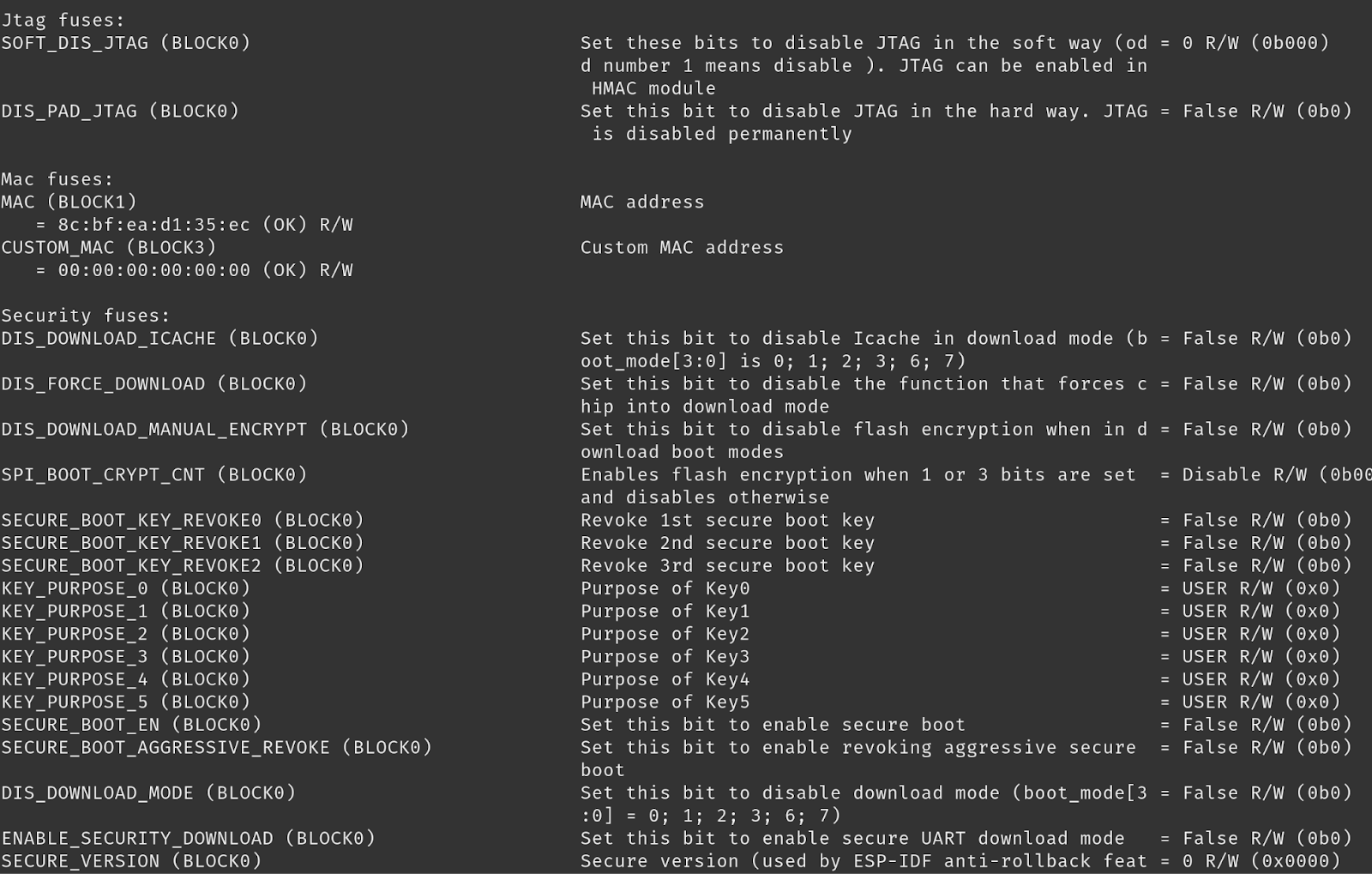

With Espressif’s espefuse we can review several of the security settings which may be enabled by developers. espefuse is a tool which facilitates the communication with Espressif chips, “for the purpose of reading/writing (“burning”) the one-time-programmable eFuses”.

Once we put the device into the bootloader mode which we described earlier, we can run espefuse on the chip to retrieve a summary of the configurations.

What we are interested in specifically are the Security Fuses, seen below.

There are several misconfigurations we can identify based on this:

- Flash encryption is disabled. But we already knew this based on our analysis of the flash dump.

- Secure boot is disabled.

- Anti-rollback protection is set to disabled—this is indicated by the SECURE_VERSION flag being set to 0.

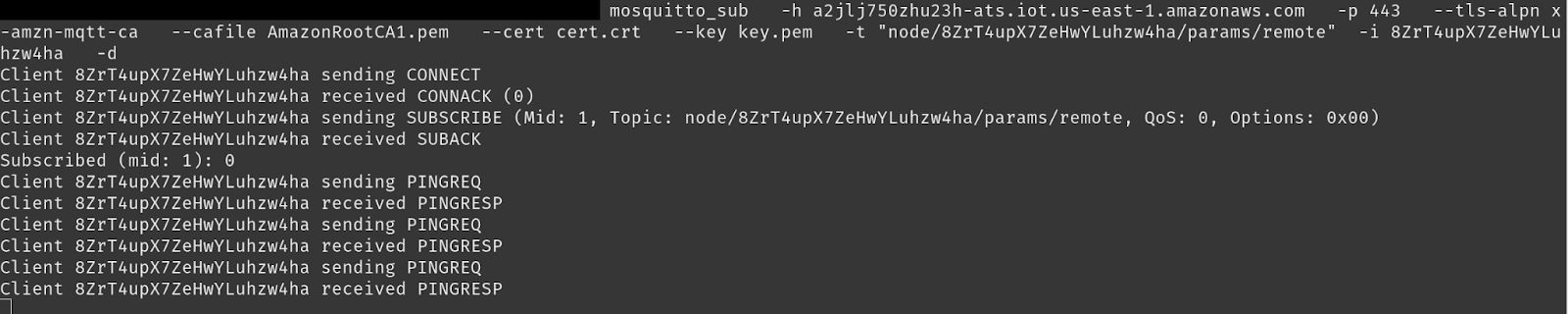

MQTT

Keen readers, or those familiar with Espressif’s offerings, would have noticed the mention of Rainmaker in many of the MQTT calls shown in the UART logs. For us, it was a new technology. But our hopes of exploiting MQTT as we had with the Furbo were quickly dashed after doing a bit of research. Espressif offers ESP Rainmaker as a SaaS solution to vendors using the ESP32 chip as their base platform. The Rainmaker MQTT solution has a limited number of topics available to publish to, and even fewer to subscribe to. The full “API” docs can be found here.

The access control mechanisms implemented for devices are quite strict. Each device is assigned a unique NodeID with which their RSA private key is associated. This meant that we could publish and subscribe but only as our device. Not nearly as interesting as being able to subscribe to the root topic of a MQTT server.

Here’s what it looks like once you’ve subscribed to the Rainmaker MQTT server:

Ping requests and ping responses are about as interesting as it gets. While it was a disappointment from a vulnerability research standpoint, it was highly interesting and something we would recommend if implementing MQTT on an ESP32.

Moving on to the App

So far we have familiarized ourselves with the basic operations of the device, analyzed the UART output, dumped the flash and reviewed it. This will all prove to be instrumental in the next two parts of the hacking project. In part two we will turn our attention to the mobile application where we identify a handful of vulnerabilities through static and dynamic analysis.

.avif)