Evil Cookie

Cookies are a foundational part of modern web applications, but small assumptions about how they’re parsed can lead to outsized failures. By breaking down real-world incidents, exploitation mechanics, and systemic impacts, it highlights why cookie handling is a critical but often overlooked security boundary.

Cookies are among the most common components of modern web applications. They track sessions, remember preferences, and help servers recognize users across requests. Most developers see them as harmless text strings that quietly support the user experience.In reality, a single cookie can sometimes have the opposite effect. Your website might be one cookie away from a denial-of-service (DoS) attack that locks out every user.

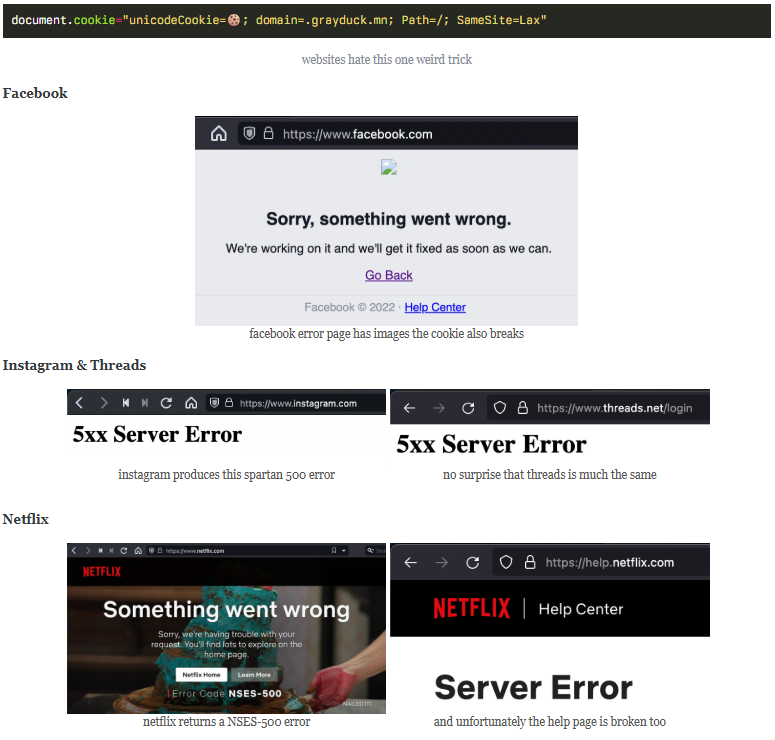

This exact issue has affected major platforms, including Facebook, Pinterest, and TikTok, as well as several other large organizations. Everything started with a single malformed cookie. This article explains how a seemingly simple cookie header can trigger large-scale outages, why this occurs, and how developers can protect their applications from this subtle yet serious risk.

Cause of the issue

The root cause of this vulnerability is surprisingly simple. Many web applications do not properly handle Unicode characters, such as emojis, in cookie values. When a cookie containing these characters is sent to the server, the application fails to interpret the value correctly. This mishandling can trigger unexpected behaviour that ultimately causes the application to crash, resulting in a denial-of-service.

While often perceived as low risk, this class of issue has affected several major platforms such as Facebook, Instagram, Netflix, WhatsApp, and Amazon, due to server-side assumptions about cookie character sets. Enforcing proper input validation and encoding is essential to avoid these types of failures.

Source: Gray Duck Software — “Handling Cookies Is a Minefield” (2024)

Exploitation

This class of bug is straightforward in concept, and that simplicity makes it dangerous in practice.

An attacker who can cause a victim’s browser to send a specially crafted cookie to your domain can trigger the parsing failure on the server.

There are multiple ways an attacker might cause a browser to include an attacker-controlled cookie, including cross-site scripting, cookie injection on a subdomain, or other flaws that let them influence the client-side environment. Below are the JavaScript examples originally used in public writeups to set the problematic cookies. These snippets are included here for transparency and discussion, not as an instruction to exploit production sites. They are shown in non‑runnable form to prevent accidental misuse:

// Example 1, benign cookie set (non-runnable representation)

document.cookie[=]"cookie[=]🍪[;] Path[=]/[;]"

// Example 2, unicode cookie name that caused deletion issues (non-runnable representation)

document.cookie[=]"\\ud800[=]🍪[;] Path[=]/[;]"

Conceptually, the attack flow looks like this:

- The attacker causes a victim’s browser to include the special cookie on requests to the target domain.

- The server receives the cookie header and attempts to parse or interpret the cookie name and value. If the parsing code is not robust to unexpected Unicode sequences or malformed byte sequences, it may throw an unhandled exception, trigger resource exhaustion, or otherwise destabilize the request handler.

- If enough requests with the offending cookie are processed, the problem can amplify to worker crashes, process restarts, or wider outage conditions.

- In some observed cases, odd browser behavior or encoding quirks made the offending cookie difficult for users to delete through normal browser UI, which prolonged disruption until the cookie was cleared by more intrusive client actions.

Because the cookie parsing happens deep in the request lifecycle, a single malformed header can cause disproportionate harm when it is processed at scale. That is the reason many high-traffic platforms saw broad impact from what looks like a trivial header anomaly.

Impact

- Widespread user disruption. A single malformed cookie can cause crashes or worker failures that affect all users, not just the account that originally received the cookie.

- Amplification potential. If an attacker can cause many clients to send the cookie — such as by posting a malicious snippet on a popular page or combining the trick with other client-side flaws — the outage escalates quickly.

- Recovery friction. In reported incidents, some browsers and configurations prevented users from easily removing cookies with unusual names, which prolonged the outage and increased the support burden.

- Operational and reputational cost. Large-scale downtime leads to emergency response cycles, revenue loss, and public scrutiny.

Conclusion

Cookies sit at the boundary between browser behavior, HTTP parsing, and application logic, where implicit assumptions about encoding and structure are common. When those assumptions are violated, even a single malformed cookie can propagate through the stack and expose systemic weaknesses. Incidents impacting major platforms show how subtle parsing discrepancies can be leveraged into meaningful security risk.

A key mitigation is strict server-side validation of cookie values before they are parsed or trusted. Cookie contents should conform to an explicit schema, including allowed character sets, encoding format, and length constraints. Any cookie that fails validation must be discarded. For authentication-related cookies, this should invalidate the session and require re-authentication, preventing malformed state from influencing application logic.

By enforcing clear trust boundaries and rejecting ambiguous input early, applications reduce exposure to parser confusion and logic flaws rooted in malformed cookies.