How Hackers Use CSS Injection to Hack “with Style”

CSS can quietly leak sensitive data, like CSRF tokens, without a single line of JavaScript. This article breaks down why CSS attacks are different from XSS, walks through a conceptual example of how these subtle leaks happen, and gives practical, prioritized steps defenders can take to lock down their apps. If you care about client-side security, this is the mental model you need.

Style is not just aesthetics

When people talk about style, they picture shoes that finish an outfit, a haircut that changes how someone carries themselves, or the way sunlight hits a café table. Style sets an impression before a single word is spoken. On the web, CSS does the same work. It controls rhythm, spacing, and emphasis; it makes a product feel trustworthy, and it shapes how users interact with content.

Because style is trusted and usually harmless, teams rarely look for danger in it. That trust is exactly what attackers repurpose.

Subtle styling rules and remote style resources can become quiet signals that probe, confirm facts, and leak small pieces of data.

These are not the loud, destructive attacks that crash a site. They are whispers, collected over time, that let an attacker confirm secrets or prepare a follow-on compromise.

This article explains how style becomes an information channel and why CSS-based probing is fundamentally different from traditional script-driven attacks. Where JavaScript exploits rely on code execution, direct data access, and observable side effects, CSS attacks operate without logic, state, or permissions, using the browser’s layout, loading, and rendering behavior as a passive oracle. The article then walks through a conceptual example showing how these constraints can still be abused to leak a CSRF token, and, most importantly, what defenders should do about it.

This is not a how-to guide. There are many ethical research write-ups and vendor posts that test these primitives in safe labs. Here, the goal is to provide defenders with an accurate mental model that enables them to identify and address risky behavior.

A concise technical orientation, without the exploit details

What CSS can do goes beyond colours and layout. Let’s consider three basic capabilities that make CSS really powerful

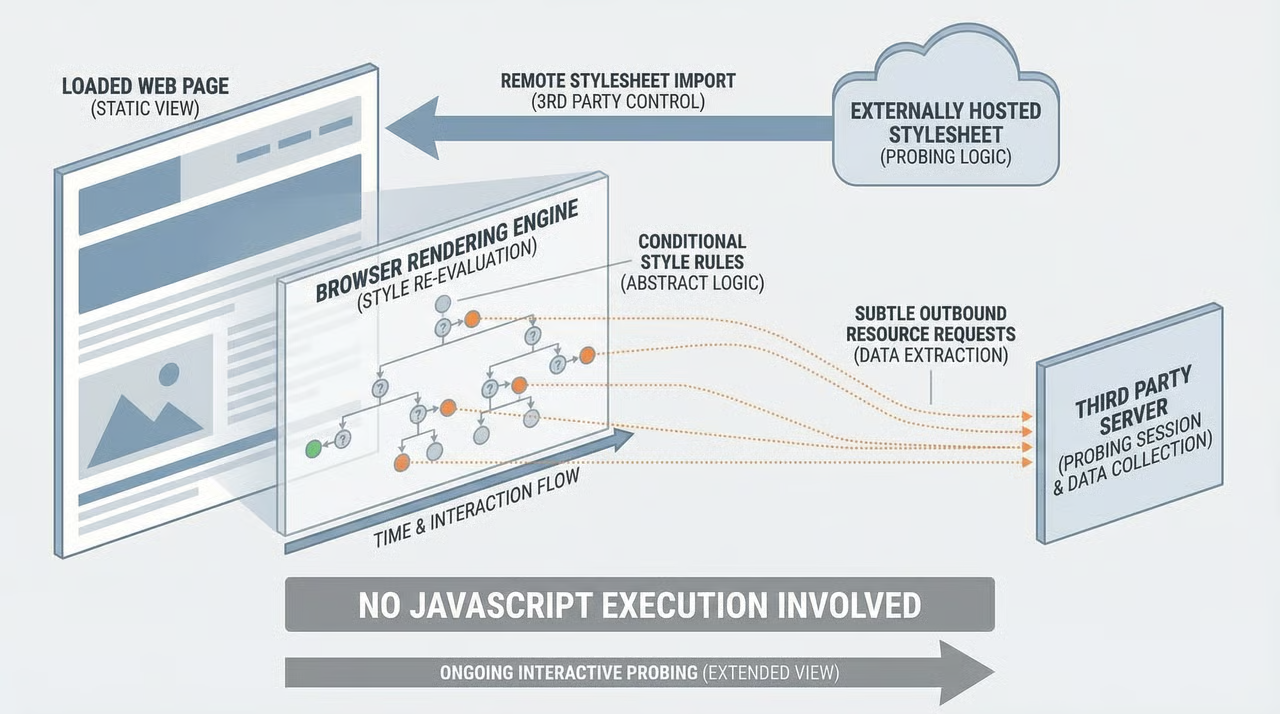

- First, modern CSS selectors and attribute matching enable styles to apply only when a specific DOM condition is met. That matching behavior is deterministic and observable by the browser. For example, selectors such as input[name="csrf"] or input[type="hidden"][data-token] match hidden form fields that may be used to hold CSRF-related values, while attribute selectors like [data-csrf^="A"] match elements whose token-related attribute begins with a given prefix. In each case, the selector applies a style only if the corresponding DOM condition is satisfied, effectively turning selector evaluation into a conditional test performed by the browser.

- Second, some style properties cause the browser to fetch external resources. A background image, an imported stylesheet, or a font reference causes an outbound request whenever the browser evaluates that resource. If an attacker controls the resource host, each fetch becomes a tiny signal, effectively a yes-or-no response to the test that triggered it.

- Third, remote styles allow an attacker to change the probing rules after a page has loaded. An attacker-controlled stylesheet imported by a page can contain many conditional rules. That turns a single-page view into an interactive extraction session, all without executing a script.

Put together, these primitives form a low-noise exfiltration channel. A selector confirms a condition, a resource fetch reports the result to an attacker, and repeated queries rebuild more complex information. New CSS features, such as variables, inline style functions, and advanced selectors, broaden the possibilities for creating these tests, making these techniques more practical on modern sites.

Why CSS injection is not just a weaker form of XSS

It is tempting to lump CSS injection under the XSS umbrella, but the practical differences matter for testing and remediation.

Script-based XSS attacks rely on executing JavaScript code in the victim’s browser. Defences against them typically focus on the JavaScript execution pipeline, such as sanitizing or removing <script> tags, enforcing strict Content Security Policies (CSP), and performing server-side input validation.

In contrast, CSS-based probes do not require script execution. They exploit the browser’s CSS parsing and rendering engine, relying on selector evaluation and resource loading side effects. Because they target a different parser and execution path within the browser than JavaScript, these techniques often bypass defences that are designed primarily to control or restrict script execution.

Because CSS probes are usually slow and quiet, they are ideal for targeted, long-term reconnaissance where loud alerts would be noticed. A successful CSS-powered leak can take time, and it can be difficult to detect because requests for static resources such as images, fonts, or imported styles are usually treated as normal, routine traffic in logs. That means defenders should treat CSS injection as a distinct client-side risk, with its own test cases and monitoring strategies.

Conceptual example, leaking a CSRF token

What follows is a high-level conceptual scenario illustrating why this is worth paying attention to and how a seemingly small leak can escalate into a significant attack. No selector patterns, payloads, or exploit techniques are provided.

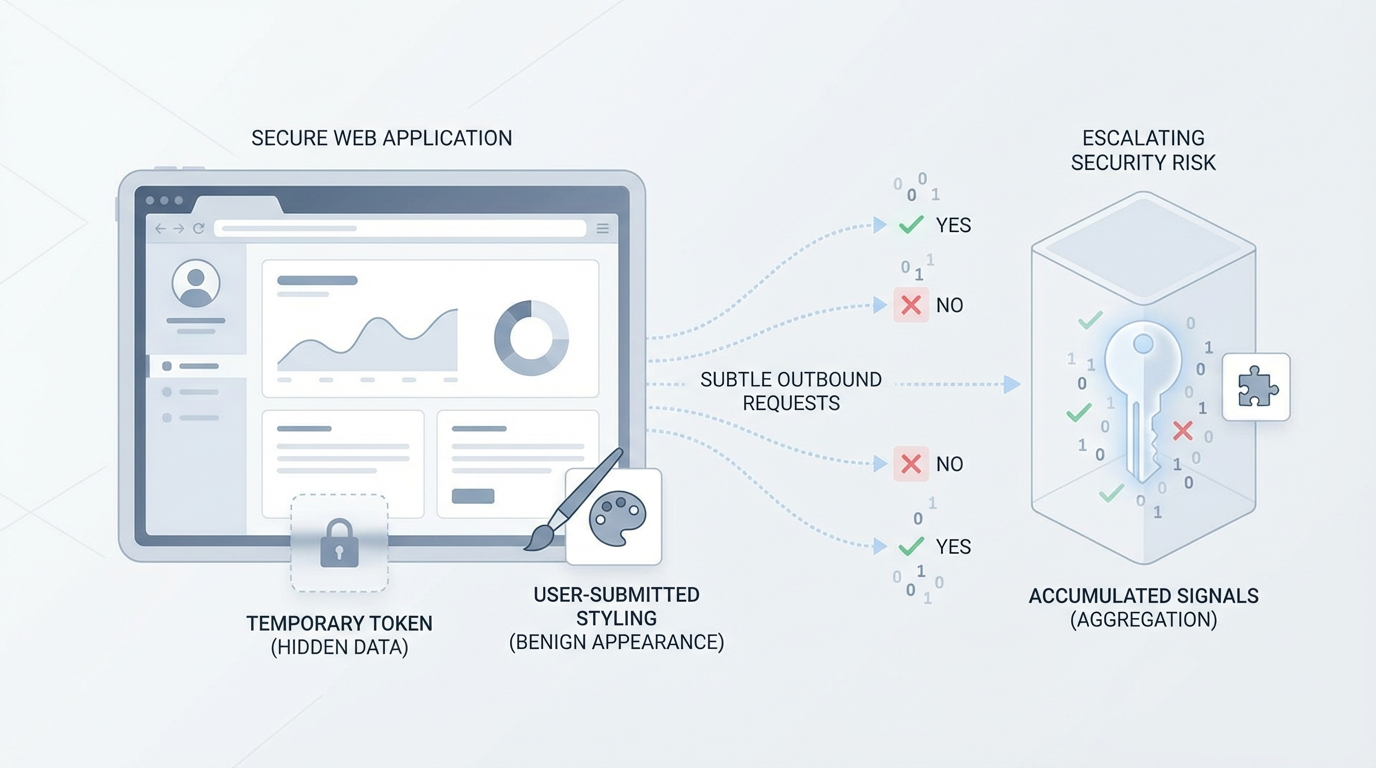

Imagine a web application that correctly blocks script injection but still renders a short-lived CSRF token into a hidden input or a data attribute on pages that authenticated users view. The application accepts user-submitted content but, for flexibility, allows only limited style fragments and a small subset of inline attributes in user posts.

A malicious user posts a styling fragment that looks harmless to designers. Conceptually, that styling can test single-character conditions in the DOM. For example, the styling can be structured so that when the first character of the CSRF token equals a given value, the browser is forced to fetch a resource hosted by an attacker. That fetch is the defender-friendly equivalent of a single yes or no answer.

By repeating many such micro-queries (e.g., testing one character position at a time), an attacker can gradually reconstruct parts of the token. Across multiple victim views or accounts, those subtle signals can combine to confirm token values. With enough confirmed pieces, the attacker can misuse the token or combine the recovered fragments with other weaknesses, such as predictable session handling or insufficient server-side validation.

The defensive lesson is not to panic, but to avoid the root cause. Small bits of sensitive data, when placed in the DOM and combined with resource-loading behaviors, are valuable in aggregate. Preventing those small leaks prevents the larger legal and operational exposure they can enable.

Practical, prioritized guidance for defenders

Here are steps teams can implement now, ordered by impact and ease of adoption.

- Do not store CSRF tokens or other sensitive secrets in the DOM. Never render long-lived CSRF tokens, API keys, or session identifiers into attributes, hidden inputs, or data attributes on pages that other users can view. Use server-side session storage and store authentication tokens as HttpOnly cookies that client-side scripts and markup cannot access.

- Remove freeform user CSS from user-submitted content. If you must allow users to customize the appearance, provide constrained theme controls, such as a palette picker or a set of pre-approved classes. Reject or sanitize raw <style> tags, @import, @font-face, and url() constructs. The smaller and more controlled the surface, the harder it is for style to be used as a signal.

- Harden style and resource policies. Implement a tight Content Security Policy for all pages that render user content. Use style-src 'self' for styles, employ nonces for legitimate inline styles if required, and restrict resource directives such as img-src, font-src, and connect-src to trusted origins. CSP is not a silver bullet, but it raises the bar and makes remote callbacks harder.

Final Thoughts

Style is a human concept that helps explain why CSS matters. It controls perception and behavior, making it a high-value target when misused. The core defensive actions are straightforward. Do not put secrets in the DOM, do not allow freeform user CSS, tighten resource policies, monitor for unexpected callbacks, and add CSS cases to your testing program.

These changes are practical and they produce immediate improvements. Start the conversation with product and design using the everyday example of a styling change. Once you have their attention, show them the technical reality and the prioritized checklist. A small amount of discipline at the interface between content and style will remove a quiet and powerful information channel from attackers.

.avif)